EU Pay Transparency Directive: What do the new rules mean for your business?

1. Introduction

In 2023, the EU took a major step towards promoting equal pay for equal work. That happened with the adoption of the EU Pay Transparency Directive (Directive (EU) 2023/970), which aims to strengthen the principle of equal pay between women and men through greater transparency. The directive responds to a persistent problem: across the EU, women earn on average about 13 per cent less per hour worked than men (in Denmark about 12 per cent less), and the pay gap has hardly narrowed over the past decade. A lack of openness around pay has long made it difficult to detect and address unfair pay differentials. With the new rules, the EU wants to shed light on pay structures in companies to promote fairness.

Fact box: The new EU directive on pay transparency was adopted on 24 April 2023. The rules are intended to combat pay discrimination and reduce the gender pay gap across the EU. In Danish law the rules are scheduled to take effect on 7 June 2026.

Even now there is a global shift towards pay transparency, with more countries introducing rules that resemble the EU directive. In the United States, around one in five workers are now covered by pay transparency requirements, for example mandatory salary ranges in job adverts. Early evidence suggests that transparency works: in both Denmark and the United Kingdom, the introduction of gender pay reporting appears to have narrowed the gender pay gap among affected employers. Employees are also increasingly expecting openness: one survey shows that 80 per cent of jobseekers will not apply for a role without a stated salary level.

In this article, we explain what pay transparency is, what the EU directive contains, when and how the rules take effect, and the implications for HR, leadership and your organisation. We also offer practical recommendations on what companies should do now to prepare, and look at how modern HR technology can help you comply with the new requirements.

2. What is pay transparency?

Pay transparency means it becomes easier for employees to gain insight into pay. In short, it is about openness around salary: who is paid what for which work, and how pay is determined. The purpose is to ensure that women and men receive equal pay for the same work or work of equal value. When pay is not secret, it becomes harder to maintain unconscious (or deliberate) differences based on gender or other factors.

Traditionally, pay has been a taboo subject in many places. Employees have often lacked visibility of colleagues’ salaries, and many employers have directly prohibited staff from sharing their pay. The directive is designed to dismantle such practices. In future, an employee must not be prevented from discussing their own salary. Greater transparency should strengthen trust in the workplace and give employees the tools to identify and challenge unfair pay gaps themselves.

Pay transparency covers several elements: openness in recruitment, internal pay information for employees, clear pay structures and job categories, and public pay reporting. Together, these measures aim to create a more transparent pay structure. The idea is that when pay is not hidden away, companies and employees can work together to ensure that work is remunerated according to gender‑neutral criteria. At the same time, it becomes easier to identify systemic differences and resolve them.

“There is not a single argument for a woman who performs the same type of work to be paid less than a man,” declared European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in 2023.

3. What does the EU Pay Transparency Directive include?

The directive contains a range of new rules for employers. Overall, it seeks to ensure greater openness around pay and to strengthen enforcement of equal pay. Below we walk through the most important obligations, point by point.

1. Pay structures and job architecture

All employers – regardless of size – must be able to group roles that involve the same work or work of equal value. In other words, you need a job structure or job architecture that groups related job functions into categories. For each category, you must describe the objective and gender‑neutral criteria that underpin pay decisions. These might include, for example, education level, seniority, level of responsibility, competencies and performance. The criteria must be applied consistently and must not favour one gender.

These criteria and principles for setting pay must be made available to employees. In other words, employees must have insight into how their pay is calculated and what is required to progress. The purpose is to avoid unexplained pay differences, so that two people in the same job category are paid based on the same neutral parameters.

Tip: It’s a good idea to start mapping your job categories and related pay criteria now. Consider how you will define “work of equal value” in your organisation. In some companies, existing collective agreement classifications can be used as a starting point. Also prepare job descriptions for each category so that the tasks and responsibilities are clear. That gives you a solid basis for objective pay evaluations.

Note: Member States may exempt very small businesses from the requirement to prepare formal pay structures. Employers with fewer than 50 employees may possibly be exempted from transparency requirements concerning pay criteria. The final position depends on the Danish implementation, but it is likely that the smallest firms will be spared the heaviest documentation duties. Regardless of company size, however, it is good practice to have clear pay principles.

2. Employees’ right to pay information

A key innovation is that employees gain the right to receive pay information. Specifically, an employee may request their own salary and the average salary levels, broken down by gender, for employees in the same category (i.e., colleagues doing the same or equal‑value work). This right applies to all employees – regardless of the company’s size.

If an employee thinks they are underpaid relative to colleagues, they can now demand comparable pay figures. The employer must provide the information within a reasonable time and in an intelligible form. If the data supplied are unclear or incomplete, the employee has the right to ask for further details and to receive a reasoned reply.

In addition, the employer must inform all staff annually that they have this right to pay information and explain how to exercise it. This ensures no employee is unaware of their options.

At the same time, employers will no longer be allowed to ban employees from discussing their own pay. Article 7 of the directive introduces a ban on pay secrecy clauses where the purpose is to enforce equal pay. Employees may voluntarily share their pay with colleagues, union representatives or others if done to advance the principle of equal pay, and they must not be sanctioned for doing so. This represents an important cultural shift: pay will no longer be a taboo subject within the organisation.

All in all, employees gain far greater insight and agency. They can take initiative if something looks skewed. For HR, this means being able to produce the requested data quickly and accurately, without breaching GDPR or other rules. This places demands on the HR function, which a capable HR system can shoulder.

3. Pay transparency in recruitment

The directive also imposes obligations before hiring new employees. Employers must inform applicants of the starting salary or the expected salary range for a role – including any relevant collective agreement provisions. This information must be provided before salary negotiations take place, for example by including it in the job advert or communicating it before the first interview. The purpose is to ensure transparent and informed negotiations, where candidates know the parameters in advance and do not enter discussions blind.

Employers will also be prohibited from asking about an applicant’s current pay or pay history. This prevents previous salary levels from following a candidate and cementing historical underpayment. All candidates should be assessed against the salary framework of the current role and their qualifications – not what they previously earned.

These requirements will significantly affect recruitment processes. Job adverts must be updated to include either a specific salary figure or a salary range for the role. Many companies have already begun indicating salary levels in adverts, as this can help attract more applicants. One survey shows that four out of five candidates ignore adverts without pay information. In other words, transparency is also good for recruitment. For HR, it creates a more level playing field in negotiations, as all candidates – regardless of bargaining power – know the salary level.

The directive also requires job adverts and job titles to be gender‑neutral, and the entire recruitment process to be non‑discriminatory. In practice, that means avoiding gendered wording and ensuring you do not recruit in ways that indirectly exclude a gender. This requirement aligns with existing equal treatment rules but now carries additional weight.

4. Pay reports and gender‑disaggregated pay statistics

One of the most far‑reaching obligations is that larger employers must regularly prepare reports on gender pay differences. These pay reports and pay gap analyses must show whether there are differences in pay between women and men across the company’s job categories. The purpose is to create a data foundation that can reveal systematic disparities.

Specifically:

- Employers with at least 100 employees must prepare a gender‑disaggregated pay report. As a minimum, this should illuminate the pay gap between women and men for the same work or work of equal value. Employees and their representatives must have access to the report, and in many cases it must also be made publicly available.

- Reporting frequency depends on company size: if you have more than 250 employees, you must report every year. Employers with 100–249 employees must report every three years. (In Denmark there is a small transitional arrangement: for employers with 100–149 employees, the requirement only applies after five years – meaning the first report, covering the 2030 calendar year, must be prepared by June 2031.) Employers with fewer than 100 employees are not currently subject to this EU‑level reporting requirement.

The reports must include gender‑disaggregated data, e.g., the average pay for women vs. men within the defined job categories. According to the directive, they should also include the share of women and men receiving bonuses or variable pay. The detailed format and content will likely be clarified further in the Danish implementing rules.

Fact box: Since 2007, Danish employers with at least 35 employees (and at least 10 of each gender) have been required to prepare an annual gender‑disaggregated pay statistic. This national rule (introduced by amending the Equal Pay Act) sought to increase focus on equal pay. Nevertheless, pay differences persist, and evaluations show only about one third of affected employers actually complied. The EU Pay Transparency Directive significantly expands the requirements and adds enforcement mechanisms to ensure the data are not only produced but actively used to promote equal pay.

5. Joint pay assessment where pay differences are unexplained

Data are of limited value without follow‑up. The directive therefore includes a mechanism that is triggered if the data reveal significant gender pay differences. If a company’s pay report shows an unexplained pay gap of more than 5 per cent between women and men in a given employee category, a joint pay assessment (also called a pay review) is required.

A joint pay assessment means that the employer, together with employee representatives, must review pay and analyse why the difference arises, and then draw up actions to address it.

Typically, three conditions must be met for the joint assessment requirement to be triggered:

- The pay gap exceeds 5 per cent between women and men within the same job category.

- The difference cannot be explained by objective, gender‑neutral criteria, such as higher education, greater responsibility or more experience in one group. It is the employer’s responsibility to demonstrate any legitimate explanations.

- The difference has not been rectified within six months of being identified in the pay report.

If all three conditions are met, the company must, within a reasonable time, carry out a joint pay assessment together with employee representatives. The result will typically be an action plan to eliminate the gender‑based pay difference. This may involve pay adjustments for the underpaid group or changes to the pay criteria to make them fairer.

6. Enforcement and reversed burden of proof

To ensure compliance, the directive also contains provisions on enforcement, burden of proof and sanctions. These strengthen employees’ legal position in equal pay cases and motivate employers to meet the requirements.

The most striking change is the introduction of a reversed burden of proof in certain circumstances. If a company has failed to meet its obligations under the directive – for example by not preparing a pay report or by refusing to provide pay information to employees – the burden of proof in any equal pay case is reversed. This means that if an employee brings a case about unequal pay, any difference between a man’s and a woman’s pay is presumed to be discrimination until the employer proves otherwise. The burden therefore lies with the employer rather than the employee if the company has not lived up to the transparency duties.

This is a significant shift, as it is normally the employee who must prove that they were discriminated against. Now, an employer that neglects transparency will need to present evidence that pay differences are due to legitimate factors and not gender. By contrast, if the employer has complied with all transparency obligations, the ordinary burden of proof (on the employee) applies.

Beyond the burden of proof, Member States must impose effective penalties for breaches, including fines. Employees who suffer loss due to unequal pay must have a right to full compensation, including back pay and damages for any non‑pecuniary harm.

From equal pay to pay transparency: The Danish Equal Pay Act guarantees equal pay for equal work, while the EU Pay Transparency Directive extends the principles by requiring greater openness. The directive obliges employers to share pay ranges, disclose salary levels in recruitment and report on pay differences. The goal is to make equal pay not only a principle but a practice that can be documented and enforced.

4. When do the pay transparency rules take effect?

When does the directive apply? The directive formally entered into force at EU level on 7 June 2023, but it must first be implemented into national law by 7 June 2026. That means Denmark must, by that date, have adopted the necessary laws or amendments so that the directive’s rules apply domestically from the same day.

In Denmark, it is expected that the government will present a bill well before the deadline. Implementation is already under way, but the precise design of the new rules in a Danish context is still awaited.

As noted, Denmark already has rules on gender‑disaggregated pay statistics, and equal pay is a requirement under the Equal Pay Act. The new EU directive will strengthen these rules and extend them with the comprehensive transparency obligations described above. So even though the principle of equal pay has been enshrined in Danish law for decades, the EU directive bolsters enforcement through greater transparency and data use.

It is therefore essential to understand which obligations may affect your company. Some apply immediately, while others phase in. For example:

- First pay report for employers with 250+ employees must be prepared by 7 June 2027, covering the 2026 calendar year (thereafter annually). For those with 150–249 employees, the first report is also due by 7 June 2027 for the 2026 calendar year (thereafter every three years). For 100–149 employees, the first report is deferred to 2031 for 2030 data (thereafter every three years). There is currently no reporting requirement for employers with up to 99 employees.

- Employees’ right to request pay information is expected to apply from June 2026.

- Recruitment obligations – pay ranges in job adverts and the ban on asking about previous pay – must be implemented immediately, i.e., adverts posted after entry into force must follow the new rules from 2026.

In practice, Danish employers can expect to use 2025 and the first half of 2026 to transition. The directive requires Member States to ensure that analytical tools or methodologies are available to assess the value of work and to provide particular support to smaller employers under 250 employees in meeting the requirements.

For Danish business leaders and HR directors, the message is clear: there is not long before the new rules take effect. Use the time to get ahead. As you will see in the next section, the implications are far‑reaching. Fortunately, there is still time to prepare and to turn the requirement into an opportunity for improvement.

5. What are the implications of pay transparency for my organisation?

The coming rules will affect the organisation across functions. HR will receive new tasks and greater responsibility for data handling and equal pay. Leadership may need to rethink pay strategies, allocate resources for pay adjustments and manage greater transparency towards both employees and the public. For the organisation as a whole, culture and employee dynamics may shift as pay becomes a more open topic. Below we outline the main implications for each stakeholder group:

HR function:

HR will be the hub of implementation. HR must develop or update internal policies and procedures to comply with the new rules. HR must also produce the annual/three‑yearly pay reports and analyse the data. That demands strong HR analytics and data processing skills – something not all HR teams possess today. Many will need support from business intelligence or external consultants to produce actionable reports. Administration will inevitably grow, and the Confederation of Danish Industry has warned of “significant administrative burdens” from the new rules, especially for small and medium‑sized enterprises. A comprehensive HR system is therefore a sound investment for the future.

Leadership:

Leadership will likely need to shape pay strategy with equal pay and transparency in mind. That may mean setting more centralised pay frameworks to avoid arbitrary differences. If analyses reveal unexplained disparities, the company may need to raise certain employees’ pay to correct them, which requires a reassessment of budgets. This costs money and must be reflected in salary budgets going forward.

Leadership must also prepare for a culture shift: as pay becomes less secret, difficult questions may arise. For example, high performers who discover they are below the category average may seek explanations or higher pay. Research indicates that pay equity can strengthen engagement and support broader DE&I efforts (diversity, equity and inclusion). Leadership should therefore see the strategic picture: compliance is not only a box‑ticking exercise but can also positively influence culture and reputation.

Organisation and employees:

For employees, the rules can increase trust and a sense of fairness – if handled well. When pay is less mysterious, the risk of mistrust diminishes. That can create a healthier work environment and higher motivation, particularly among women who might otherwise feel undervalued. Over time, greater openness can also shift company culture to be more performance‑ and competence‑oriented, as pay differences must be justified by competencies and results.

There is, however, a potential downside to manage: during the transition, transparency can create dissatisfaction if imbalances come to light. Employees who find themselves below colleagues may become demotivated if issues are not addressed. It is therefore critical that leadership recognises and corrects any disparities.

In short, change management will be vital. Introducing pay transparency is comparable to other major organisational changes – it requires planned change. HR, leadership and employees all need to be part of the journey to make it a success. Companies that approach it proactively may emerge with a stronger, more coherent pay policy and a better employer reputation. Those that lag behind risk internal frustration and quick‑fix solutions.

“Pay transparency is a step toward greater pay equity, a step that begins with planning. With 4PLAN HR, pay transparency becomes part of personnel cost planning and thus a proactive element of HR strategy.”

– Hanns‑Dirk Brinkmann, Managing Director, S4U

There are both challenges and opportunities ahead. Fortunately, you do not have to wait passively. There are many practical steps companies can take now to get ready.

6. What practical steps should companies take now?

Although the new rules do not take effect until 2026, it is wise to start preparing now. Compliance requires substantial work, and by getting started early you can get ahead and achieve strategic improvements. Here are concrete steps HR and leadership should consider:

Review your pay policy and criteria: define objective pay criteria for all roles. What do you reward – education, experience, performance, responsibility level, etc.? Ensure criteria are clear, sound and gender‑neutral. Document them in writing. If you already have a pay policy, update it so it is transparent and understandable for everyone.

Map job categories (job architecture): identify which groups of roles in your organisation perform the same or equally valuable work. Create a job categorisation, e.g., by function or level. Prepare job descriptions for each category to clarify responsibilities and tasks. This will help you identify “equal work” and provide a common language for pay discussions.

Collect and analyse pay data: start extracting pay data from your systems and prepare an initial gender pay analysis. What is the average difference between women and men in each category, according to your own figures? Identify categories with the largest differences – and investigate why. If you find gaps above roughly 5 per cent, assess immediately whether there are objective reasons. If you cannot justify the difference, consider adjusting pay now.

Adapt recruitment practices: review your recruitment process step by step and embed the new rules. Update job advert templates to include a salary range or clear starting salary for each role. Prepare recruiters on how to communicate this to candidates. Explicitly instruct them that asking about a candidate’s current pay is no longer permitted. Some employers already choose to include salary levels in adverts.

Train leaders and communicate internally: inform all line managers about the coming rules so they are prepared. Hold workshops on how to respond if an employee requests pay information or highlights an inequality. Ensure top management communicates that the company supports the aims of pay transparency.

Get your data and IT systems in order: check whether your HR systems can extract the data needed for reporting. Typically, you need to pull pay information split by gender within categories. Consider HR‑controlling tools that can ease the workload. If you currently do everything in Excel, it will likely pay to invest in more robust solutions, as the reporting requirements repeat year after year.

Follow the legal developments: keep up to date with the implementation process. As soon as the Danish bill is published, you should understand the details. The earlier you have clarity, the better you can refine your preparations.

By following the above steps, your company will be in a much stronger position when June 2026 arrives. Many of these measures are not just about compliance – they can improve HR management in general. You will gain better control of your pay structure, clean up any disparities and potentially improve employee satisfaction along the way.

7. Is there a digital solution to comply with the directive?

Meeting the new requirements can become a heavy burden. However, there are tools designed to reduce the administrative load linked to HR controlling. Modern HR technology can automate and streamline many tasks that would otherwise require manual work and spreadsheets. Employers with many staff or complex pay structures, in particular, can benefit from implementing a robust HR and pay analytics system before 2026.

Here are ways HR tech can support your pay transparency efforts:

- Centralised pay database: an HR system can serve as a single source of truth for all pay data, making it easy to retrieve accurate average pay figures per category without rummaging through multiple spreadsheets.

- Built‑in job categorisation and structure: some HR solutions allow you to set up job architecture in the system – for example, assigning each employee a job code or category. That makes it easy to segment data in the way the directive requires.

- One‑click pay reports: rather than compiling reports manually, a good HR‑controlling system can generate ready‑made pay reports. For example, it can automatically calculate the gender pay gap for each job category.

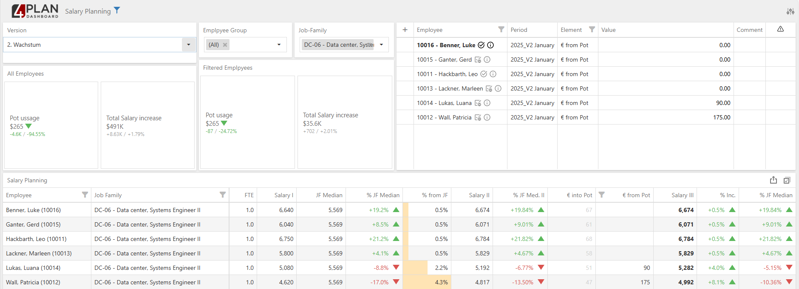

- Forecasting and scenario planning: if your analysis reveals gaps, HR tech can help simulate solutions. Some systems include scenario planning modules where you can adjust pay virtually and see the impact on key figures immediately. That makes it easier for leadership to decide which pay adjustments are needed to reach specific targets.

- Documentation and audit trail: an HR system records the history so you can always document which data a report is based on and how categories are defined. In this way you build organised documentation for your pay structure and practices.

- Manager dashboards: dashboards let managers track their team’s pay levels against other teams and view gender‑split charts, building awareness of equal pay within each area of responsibility.

A concrete example of a solution that addresses many of these needs is Timegrip. With 4PLAN you get an all‑in‑one platform for advanced HR management, offering precise and efficient workforce planning, budgeting, forecasting and HR analytics. With a tool like this you can connect staff scheduling with financial management. In practice, that means HR and finance can jointly monitor labour costs, allocate budgets fairly and spot anomalies.

Specifically for pay transparency, this HR‑controlling solution helps you quickly categorise employees, set up KPIs for gender‑split pay differences and generate the reports the directive requires – all in an intuitive way. The system typically integrates with your existing time and attendance or payroll systems, meaning the data you need are automatically up to date and consistent. This is a major advantage when, for example, you need to inform employees about their salary levels: with a few clicks, HR can produce a report for each employee with their current pay and relevant averages ready to share.

Timegrip’s 4PLAN solution is designed with usability and your specific needs in mind. That means even employers without large HR departments can benefit from automated HR controlling. By using such a tool, you can avoid a large portion of the administrative workload, allowing HR to focus on acting on the results rather than spending all their time collecting them.

“Complying with the new rules does not have to be an administrative burden if you have the right systems in place. Modern HR technology can automate data collection and reporting, provide real‑time transparency and support leadership in making data‑driven decisions. That frees time for HR to focus on strategically advancing equal pay and wellbeing.”

– Hanns‑Dirk Brinkmann, Managing Director, S4U

Examples of concrete 4PLAN features include:

- Budgeting and pay forecasting: plan labour costs ahead and see how changes affect the bottom line.

- Scenario analysis: test salary development scenarios and visualise the impact immediately.

- KPI dashboards: track key HR and pay metrics, including gender‑split statistics and turnover rates, so you can monitor equality progress continuously.

- Integrated reporting: generate reports from real‑time data that can be shared with the board, employee representatives or the public.

- User‑friendly interface: advanced analyses are presented in an accessible visual format, so you don’t need to be a data expert to interpret them.

Contact Timegrip today for a no‑obligation conversation about how we can help you.

8. Conclusion: Get ready for pay transparency in 2026

The EU Pay Transparency Directive marks a new era in which openness about pay becomes the standard. For Danish employers, that means new obligations – but also new opportunities. The core of the directive is simple: equal pay for equal work must be demonstrable and deliverable. Transparency is the means to that end.

For HR leaders and managers, there is substantial work ahead in reviewing pay structures, establishing systems and possibly adjusting salaries. The reward is a fairer and more attractive workplace.

Internationally, the direction is clear: transparency is on the rise. Countries such as Iceland have gone even further than the EU and require certification of equal pay, which has almost eliminated the unexplained pay gap there. Across the EU, the 27 Member States will now move in the same direction via the directive.

It is worth remembering why all this is happening: because society no longer accepts unexplained pay differences. Ultimately, this is about people and fairness. When two people work equally hard and create the same value, they deserve the same pay – that is common sense and good ethics. But it takes transparency to ensure practice follows principle.

In short: now is the time to act. 2026 is approaching fast, and the pay transparency directive is happening. It is therefore strategic to get ahead. Draw on the experience and data available (both internally and from other countries), get your pay structure in order, involve your organisation in the process and harness the helping hand of technology.

Do you want to meet the requirements of the Pay Transparency Directive? Contact Timegrip for free today.